The Computational Theory of Mind: Classicalism, Connectionism, and AI

Given that the focus of this part of the blog will be the relationship between AI, cognitive science, and various research questions, we should begin by discussing the foundational idea behind cognitive science – what is known as the computational theory of mind (or, cognition) – and in particular, work our way to the competing versions of this theory; classicalism, endorsed traditionally by cognitive scientists and linguists, and connectionism, which undergirds contemporary approaches to artificial intelligence.

This approach to studying the brain, cognition and behavior emerged in the 1950s, after the explosion of progress in computer science. Alan Turing was a main proponent of the theory, devising his Turing test for artificial intelligence. In addition, the decline of behaviorism and mind-body identity theory (both of which came under significant philosophical objections and theoretical criticisms) brought about functionalism, proposed by Hilary Putnam, which was an approach to studying the mind by studying its functions.[1]

Turing Machines and Functionalism

Functionalism is based around the idea of “multiple realizability”, in that the same function, once clearly defined, can be instantiated by any number of different things. The original Turing machine, for example, could be realized by any type of machine as long as it is able to carry out the intended function. Nowadays, a Turing machine could be implemented fully digitally. The upshot is that function is emphasized, and not material composition.

That is, things like “thinking” or “visual recognition” should not merely be identified with particular biological events like nerves firing, but rather by their function. Visual recogition, for example, takes in particular input data, ‘processes’ it, and by comparing it with existing memories, is able to recognize certain shared elements. Under this definition, such behavior can be multiply realized – you don’t have to have a retina and visual cortex in order to see; anything that is able to perform these particular actions could be said to be capable of visual recognition.

As Turing himself wrote:

"May not machines carry out something which ought to be described as thinking but which is very different from what a man does?"[2]

Implicit in this is the idea of multiple realizability, that biological structure or even similitarity matters little as long as a common function is accomplished. What are the common elements between what we do when we think, and what a machine could do, that would cause us to describe it as “thinking”? That is the fundamental question.

By moving away from biological restrictions and focusing instead on the functions the mind carried out, an easy analogy could be drawn to a computer, which is instantiable in any sort of machine (from very simple to very complex).

A Turing machine, as originally devised, is a rather simple input-output program that accomplishes a certain task (called symbol manipulation). For example, “if position #4505 contains 0, obey the next instruction stored in position #6707, otherwise move on to position #7820”. Put in pseudocode, it would resemble an if-then statement like so:

if position[4505] == 0:

go to position[6707]

else:

go to position[7820]

Turing then compares this to a real-life example of ‘instruction following’, and this is where we can begin drafting the theory itself:

"To take a domestic analogy. Suppose Mother wants Tommy to call at the cobbler's every morning on his way to school to see if her shoes are done; ... she can stick up a notice ... in the hall which he will see when he leaves for school and which tells him to call for the shoes, and also to destroy the notice when he comes back if he has the shoes with him."[3]

So, again, writing this in pseudocode gets us a set of nested instructions like this:

while shoes != done:

call

if call == true:

get shoes

if get shoes == true:

shoes = done

Here, Turing remarks, “the reader must accept it as a fact that digital computers can be constructed … according to the principles we have described, and that they can in fact mimic the actions of a human computer very closely.”[4] Turing’s point is that any human behavior can in theory be made into some sort of function, and thus, in theory, a sufficiently complex computer could (and would) be doing tasks that resemble human ones.

$\longrightarrow$ We don’t want to say that functionalism and computationalism are one and the same thing (something the cognitive scientist and philosopher Jerry Fodor expressed concern about), but merely to draw the connections and similarities between the two. Functionalism is a good way to understand how the abstractions of computational processes can be applied to the mind.

The Computational Theory of Mind: Classicalism

So, following this, human cognition could be seen as a computational or algorithmic process – it seems to take some input and produce some output, with clearly defined instructions in between.

In 1961, Allen Newell and Herbert Simon posited the “General Problem Solver” (GPS). This was an attempt at trying to reproduce the process of “thinking” in computational form. For example, they had a person think out loud as they went about solving a particular logic problem, like reversing a logical expression.

Say we want to solve a simple math problem: $ 2x = 4$. First, we isolate the variable and then perform the same operation to the other side of the equation – divide by 2 – which yields us our answer. Put into an algorithm:

1: Start with a few things: the number 1, the rule of division

2: Set up our equation: 2x = 4.

- where 2 is (1 + 1)

- 4 is (2 + 2), or, (1 + 1 + 1 + 1).

3: Isolate the variable by dividing by 2.

4: Divide the other side of the equation by 2.

5: Arrive at our correct answer of x = 2.

If we were to implement this on a computer using a programming language, we would do something very similar. Starting with a few given symbols and rules (numbers and the rule of division) we could easily implement the above steps. Thus, by doing this, human thinking just is a type of symbol manipulation: symbols represent information, rules are the process by which those symbols are manipulated. This led Newell and Simon to state outright:

We can postulate that the processes going on inside the subject... involving sensory organs, neural tissue, and muscular movements controlled by the neural signals – are also symbol-manipulating processes; that is, patterns in various encodings can be detected, recorded, transmitted, stored, copied, and so on, by the mechanisms of this system.[5]

Examples

Let’s look at a few more (simplified) examples to see why one might conceive of the mind and cognition as computational processes.

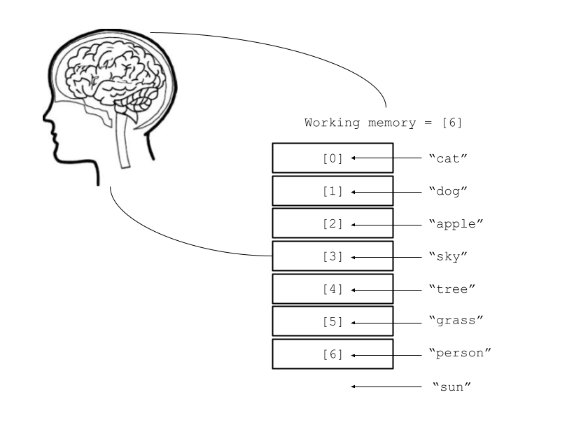

One good example to start with is George Miller’s famous hypothesis: working memory is around seven items.[6] For example, suppose you are at the park and want to memorize several things you see, taken as the following set: $\text{{cat, dog, apple, sky, tree, fruit, person, car}}$

The average person will not be able to memorize these in a short-term, working memory way, given that the set contains 8 items.

A basic schema imagining working memory as an array capable of storing seven items. The 'array' can then be used for storage and recall.

“sun”, the eighth item, has no place in the array, and thus is left out of the working memory, which would corresponod to a failure to remember.

But if we decrease the size to 6 or 7, a person typically will be able to memorize them in a short-term sense and perhaps transfer the information to elsewhere (this is, incidentally, why authentication confirmation codes are around six to seven digits).

There are other, similar experiments: in one task (Atkinson et al. 1976), subjects were tested on numerosity judgements by their ability to determine the number of some specific items displayed to them. The participants were able to judge the presence of four items quickly and accurately, while performance dropped rapidly on five items or more.[7] This also applies to our olfactory judgements, as another experiment (Livermore et al. 1996) reveals a limit in the ability to distinguish different odors (3-4 items). There are more experiments which describe other interesting, discrete limitations on our abilities, and we should wonder why this is the case. As one of the researchers put it, “the results indicated this … could not be increased by training. Therefore, the limit may be imposed physiologically or by processing constraints.”[8]

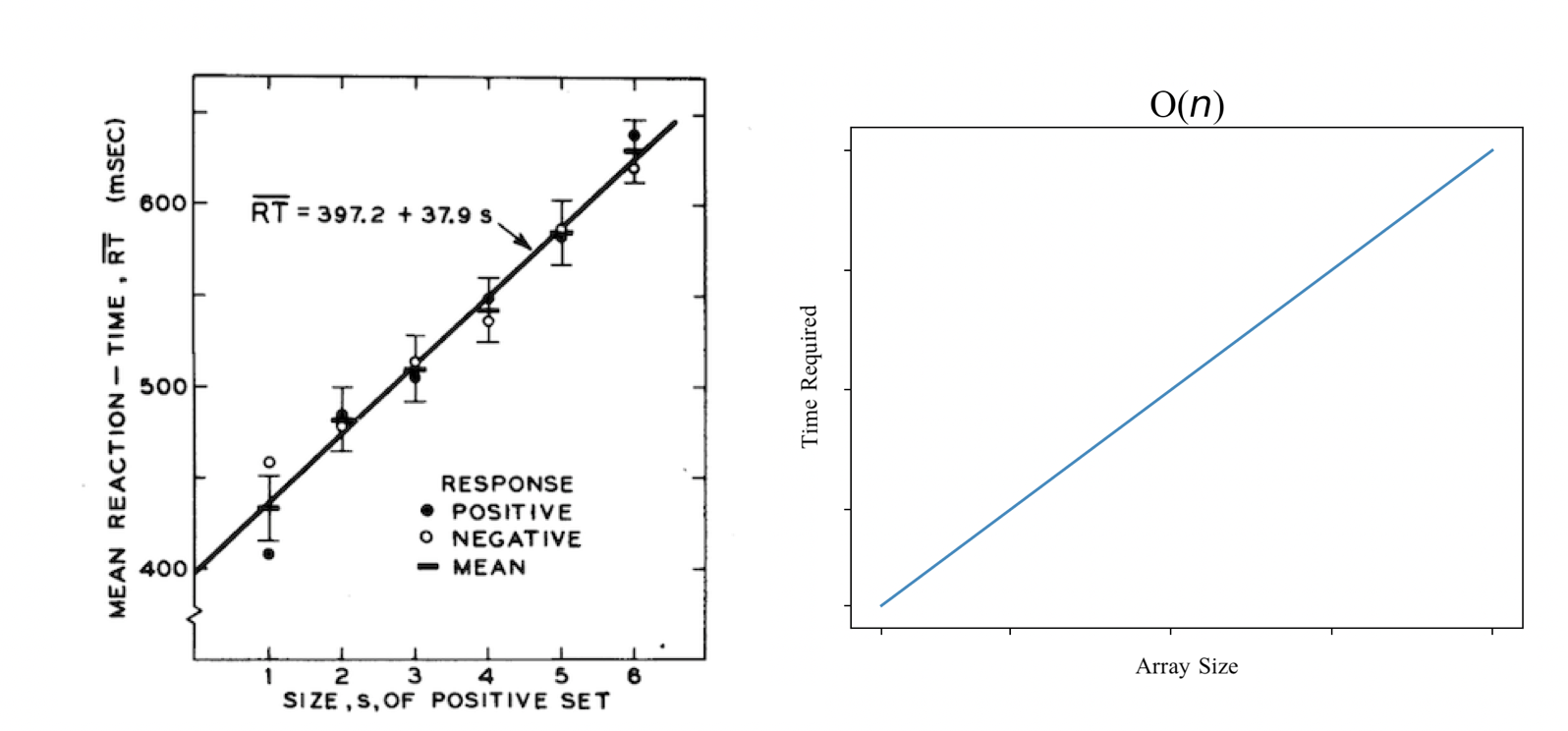

Next, let’s turn to Saul Sternberg’s work on memory ‘scanning’, from the 1960s. Assume that we do store items in our memory in array-like fashion. Now, say we want to retrieve certain elements from these memory arrays in order to answer questions like, “was $x$ on the list?” Computationally, a basic algorithm we might consider using is linear search, which involves traversing the entire array and checking each element to see if it matches what we want. Sternberg wanted to test whether humans do the same, and if so, what strategy we might use when we retrieve data from something stored in our memory. He found that the amount of time it took for subjects to recall whether a given item was in a list they had memorized increased proportionally to the length of the list:

The results of the memory scanning experiment, from Sternberg (1969), compared to an algorithm with linear time complexity.

If one were to use linear search on a computer to search an array, terminating the search once the desired item is found, it generates a very similar graph, where search time is proportional to the array length – a time complexity of O($n$) – which suggests that we really are doing something like ‘traversing’ a list in our memory using linear (what Sternberg called ‘serial’) search. This is more direct evidence for the idea that the mind works like a computer, or, as a stronger conclusion, that it is a kind of computer.[9]

Another interesting phenomena that lends itself to a computational model of the mind is Rodrigo Quiroga’s (more recent) idea of single-neuron representation, or “concept cells”. This is when a single neuron, at least as it appears to researchers, is responsible for the storage and representation of one particular thing or concept. For example, a single neuron reacts specifically and solely to information about a celebrity, or one’s grandmother. It reacts specifically to the phenomena even multi-modally – meaning that single neuron will react to same stimuli in different forms:

The neuron fired, from a nearly silent baseline, selectively to pictures of Luke Skywalker from the movie Star Wars..., his name written on the computer screen... and his name pronounced by a male and a female synthesized voice.[10]

This plays into an almost naive view of the mind as a computer, where each neuron is like a file, storing particular information about some particular thing, what could be termed a “symbol”.

All of this points towards what we can broadly refer to as the “computational” theory of cognition. It’s under this backdrop that cognitive scientists approached studying cognition, especially in the field’s first few decades. The brain appears to be some sort of computer, carrying out functionalizable processes and in many ways resembling actual computers. But it was taken a step further; it isn’t merely that the brain and cognition resembled a computer, but that it literally was a kind of computer. Some took this rather far (like Jerry Fodor), positing that the brain must have a CPU, a storage mechanism, and the like, but in general: cognition could be seen as manipulation – via rules – of discrete symbolic representations (concepts and other objects of thought).

Connectionism and Artificial Neural Networks

A major shift took place when a competitor to the classical theory emerged: connectionism. Some felt that the computational theory of mind was a bit too abstract; it didn’t really follow neuroscience, as a Turing machine hardly resembled a brain in anything but the abstract sense. Another problem with the computational view is that programs tend to be very ‘brittle’; they either work or they don’t (due to, say, a bug). But the brain is not like this – a simple shift in an image is not enough to throw us off entirely, as our ability to recognize objects is much more robust. However, whether this idea actually applies to neural networks is a separate question, one we will explore later; ironically, they may be just as brittle as any other computer program.

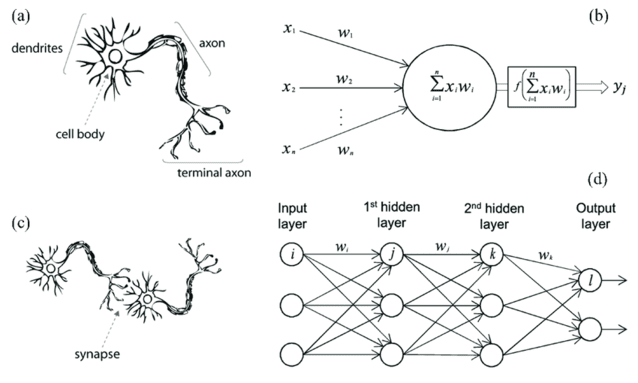

The theory states that the brain acts akin to a computer; the brain and neural circuits throughout the body form a type of connective network. Using some type of input-output mechanism, information can be transferred via complex pathways, or can be represented physically somehow, like how a computer stores information in the hard drive. In the case of the brain, this computer would be extremely complex. Each neuron could be defined as some mathematical function, taking in inputs and producing some output.

Frank Rosenblatt, in his seminal paper titled, “The Perceptron: A Probablistic Model for Information Storage and Organization in the Brain”, proposed exactly this – a way to mathematically represent the behavior of a neuron probabilistically, particularly in a way that could be used computationally:

The theory has been developed for a hypothetical nervous system, or machine, called a perceptron. The perceptron is designed to illustrate some of the fundamental properties of intelligent systems in general, without becoming too deeply enmeshed in the special, and frequently unknown, conditions which hold for particular biological organisms. The analogy between the perceptron and biological systems should be readily apparent to the reader.[11]

And in another work, he adds:

Perceptrons are not intended to serve as detailed copies of any actual nervous system... more likely they are extreme simpliciations of the central nervous system in which some properties are exaggerated and others suppressed.[12]

In other words, one can represent some of the functions done by the “brain”, but in a general way that need not worry about the specifics of particular biological structures, some of which might not even be known (as is the case now, and certainly was the case when Rosenblatt published the paper). However, as he notes, these similarities are enough that a person will be able to recognize them.

A comparison between a biological neuron and neural connection with an artificial neural network. The image attempts to draw an analogy between the biological neuron and the computational unit. A) represents a neuron, B) represents the computational version, C) represents two connected biological neurons, and D) represents an artificial neural network. From Zhengzu et al, 2020.[13]

The number of neurons in the brain is upwards of some 80 billion, but in theory, this could be modeled precisely by a complex, connected network of computational units (given enough computational power).

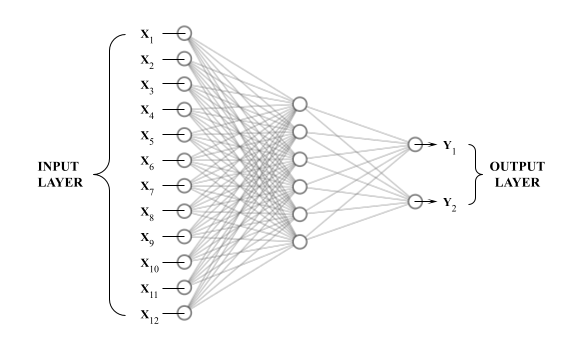

A fully-connected neural network can support an unlimited number of inputs, hidden layers, and outputs, each layer connected to the previous one.

Such a connectionist theory undergirds the current-day deep learning approach to intelligent systems. The idea is to mimic a very closely connected network of neurons in order to produce highly complex input-output systems. In this case, simulating the functions and behavior of the brain would merely be a matter of scale and computational power, and in theory, any function of the brain could be computationally recreated. The output of such systems is probabilistic, but serve as a universal functional approximator and are thus, in-principle, capable of fitting to any problem.

In this sense, connectionism is in stark contrast to the classical view: there are no rules, representations, or anything else. There are only the neurons and their weights. “Following a rule”, for example, would instead be represented as a neural network outputting in a pattern which we recognize as conforming (as an approximation) to a rule – for something like $ 2 + 2$ would be considered solved if the network outputs 4, and it would be said to have “learned” the rule of addition if it outputs the correct answer for any given input problem, not because actually represents the numbers and manipulates them according to the ‘rule’ of addition.

Thus, in this model, most cognitive capacities are emergent phenomena, arising as descriptions of outputs of the patterned firing of different sets of neurons. This has led some to describe neural networks as a “black box”, in which we have little to no idea what is going on at a lower-level as the network back-propogates over a dataset. The mystery only increases with scale: the more images or words the network processes, and the more layers and nodes the network has, the less clear idea anyone has of what exactly is going on (or, importantly, what exactly is going wrong.)

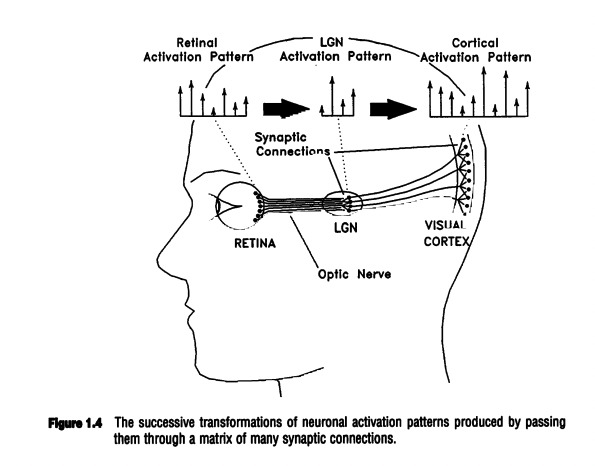

Paul Churchland imagines the visual system to be a highly complex neural network. From The Engine of Reason[14]

—————

Although connectionists would admit that such neural networks are not complete models of the brain, some posited that their models closely resembled real cogntiive activity.

For example, David Rumelhart and James McClelland worked on connectionist models in the 1980s that attempted to learn certain aspects of language. In normal language development, children exhibit what is called the “over-regularization” effect: when first learning language, they tend to conjugate the past-tense on irregular verbs correctly (regular verbs being conjugated by simply adding -ed at the end, irregular verbs being words that do not follow this rule). However, after some time, they begin to make errors. Instead of conjugating come as came, for example, they might mistakenly use the regular conjugation and say comed; eat may become eated, and so on. After some more time, they tend to again conjugate the tense on irregular verbs correctly.[15]

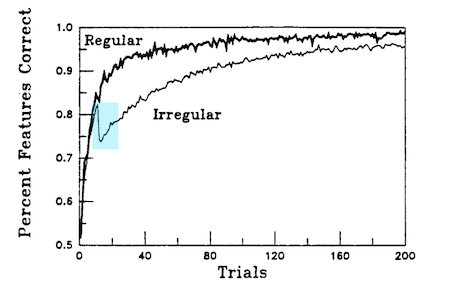

If this phenomenon is modeled by age on the $x$-axis and correct conjugation on the $y$-axis, it roughly appears as a U, which led it to be called the “U-shaped development”. When Rumelhart and McClelland trained their connectionist models, it appeared, fascinatingly enough, that the networks followed this same learning trajectory (as well as some other aspects of children’s behavior.[16]

The connectionist model appears to exhibit the overregularization phenomenon for irregular verbs (Rumelhart & McClelland 1986).

This increased the plausibility that connectionist models more accurately describe human cognition – it avoids entirely the question of what exactly rules and concepts might be and how to represent them computationally or neurally, and seems to (at least generally) more closely model what we learn about the brain from neuroscience.

In the time since, the huge increase in computational power has allowed connectionism to flourish. Larger and larger models can be constructed – what we now call “deep” neural networks – allowing networks to become massive and process huge datasets. Although it is perhaps surprising that simple back-propogation algorithms (what amounts to giant curve-fitting) are capable of ‘learning’ all kinds of topics, deep learning has established itself as the cornerstone of contemporary AI.

Modeling Algorithms as Various Computational Theories

As we’ve seen, computational models of cognition can be implemented in either form: classical or connectionism (or, as some have said, both). To see why, let’s consider another popular learning algorithm: reinforcement learning, which formalizes an essentially classical behaviorist approach. In particular, it draws on the concept of operant conditioning and association, as described by the influential psychologist B.F Skinner in his 1938 book The Behavior of Organisms.

In this model, behavior is thought to occur as a result of repeated interactions between an organism and its environment, in which the organism incrementally adapts its behavior as a result of consequences, eventually associating the correct response with a given stimulus. Operant conditioning uses behavior-reinforcing (reward) or behavior-suppressing (punishment) in order to optimize a particular behavior. Behavior, then, under Skinner’s theory, can be seen as an optimization, achieved by maximizing reward and minimizing punishment for some particular task.

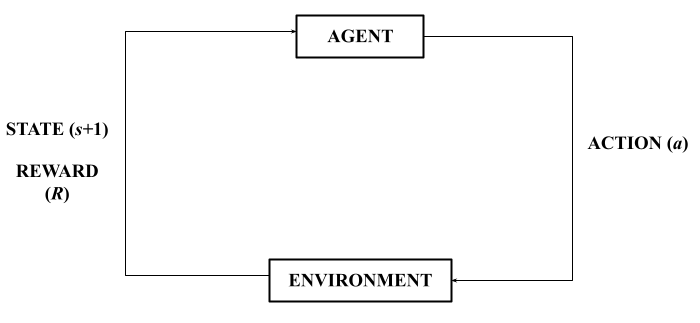

Reinforcement learning involves an interaction between the agent and its environment, with a reward function adjusting the agent's actions based on environmental 'feedback'.

Reinforcement learning follows the basic idea and formalizes this process into an algorithm. An agent in some state $s$ performs an action $a$ – often starting with random actions – either to receive some reward or some punishment $R$, until the behavior of the agent (over many, many training sets) is optimized (measured by some value $V$) for the particular task in the given environment. For any action in a given state:

\[V = R(s, a)\]In this sense, it can be adopted by either theory. Classicalism will formalize these steps and provide the agent with the necessary primitives: actions, values and the like, while connectionism (as evidenced in deep-Q learning, for example) will simply provide the agent with feedback, calculated via back-propogation.

Conclusion

To conclude: we saw how the computational theory of mind/cognition is a general thesis that developed along with functionalism, an attempt to see cognition as a computational process that could differ in its medium as the underlying action remain the same. We also saw how, within the computational theory of cognition, there are several competing views. The two main ones are, as we saw, classicalism and connectionism. All contemporary cognitive scientists are computationalists (or, I suppose, they should be), but beyond that, they differ. Thus, any given model of behavior or learning can be implemented by either version of the computational theory.

Classicalism eventually fell out of favor in the shadow of connectionism; however, connectionism isn’t without serious and very difficult problems of its own. But that will have to wait for another post.

References:

- See Robert M. Harnish, Minds, Brains, Computers: A Historical Introduction to the Foundations of Cognitive Science (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000), pg. 185-186.

- Alan Turing, "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", Mind, Vol. 59, No. 236 (Oct., 1950) pg. 435

- Alan Turing, "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", pg. 438

- ibid.

- Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, "Computer Simulation of Human Thinking." (1961), Science, 134, pg. 2012

- George Miller, "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information" (1956), Philosophical Review, 63, pg. 81-97.

- Atkinson, et al. "The magic number 4 ± 0: A new look at visual numerosity judgements" (1976), Perception, 5(3), 327–334.

- Livermore, et al. "Influence of training and experience on the perception of multicomponent odor mixtures" (1996), Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 22(2), 267–277; see also, Simons, et al., "What is magic about the magical number four?" (1982), Psychol. Res 44, 283–294.

- Saul Sternberg, "Memory Scanning: Mental Processes Revealed by Reaction-Time Experiments" (1969), American Scientist, 57, pg. 427.

- Rodrigo Quiroga, "Concept cells: the building blocks of declarative memory functions." (2015), Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13, pg. 590; see also Quiroga et al, "Explicit Encoding of Multimodal Percepts by Single Neurons in the Human Brain." (2009), Current Biology, pg. 1308-1313.

- Frank Rosenblatt, "The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain." (1958), Psychological Review, 65(6), pg. 387

- Frank Rosenblatt, Principles of Neurodynamics: Perceptrons and the Theory of Brain Mechanisms (Spartan Books, 1962), pg. 28

- Zhenzhu Meng, Hu Yating, and Christophe Ancey, "Using a Data Driven Approach to Predict Waves Generated by Gravity Driven Mass Flows" (2020), Water 12, no. 2:, pg, 600.

- Paul Churchland, The Engine of Reason, The Seat of the Soul (MIT Press, 1995), pg. 10

- Gary Marcus, et. al, "Overregularization in Language Acquisition." (1992), Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, vol. 57, no. 4, pg. 2.

- James McClelland and David Rumelhart, "On learning the past tenses of English verbs", in Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition (MIT Press, 1986), volume 2, pages 216–271.