Abduction as Intuitive Reasoning

Abduction is a type of reasoning that is also known as ‘inference to the best explanation’. This entails choosing what seems to be the best explanation given some data.

Imagine, for example, it’s a cold winter day, and the ground has iced over the night before. As you reach your car, evading the ice all over the ground, you hear a loud thud behind you, followed by a person groaning in pain. You turn to see a person laying on the ground, with a solid patch of ice nearby. Their belongings are all over the ground. Based on these observations, what would you conclude? It seems the most obvious interpretation of such a series of events is that the person slipped on some ice and fell. Is it the only possible explanation? Certainly not. But it is the best explanation given some set of observations or data.

If we want to be formal, we can define it like so:

- Inference to the Best Explanation: If explanation E gives the best explanation of some phenomena when compared with other rival explanations E1, . . . , En, we may accept E as true, or at least we should prefer E over E1, . . . , En.

Examples

This type of thinking can be found everywhere in our daily lives, across all types of different situations. Let’s consider some more examples:

- Doctors or other medical professionals do not have certainty behind their reasoning. Rather, they diagnose a patient based on symptoms, observations, and test results, which narrow down the options until the doctor can decide which is most likely (i.e, the best explanation).

- Criminal investigators use all the data they can to tell the most plausible story about how the crime occurred. They may only have parts here and there -- a murder weapon, partial surveillance footage, cell tower data -- and have to piece it together. Several possible theories will be proposed and then narrowed down to the best explanation.

- Scientists choose what appears to be the best theory based on how it explains the data. The Big Bang theory, famously, held out on replacing the previous steady-state view of the universe until it became more and more obvious that it did indeed explain the data better. This is generally how older theories (phlogiston, for example) get replaced by newer ones (oxygen) as more data is discovered and put into consideration. Science is built on the very idea of IBE.

Another very common use of this reasoning is in daily communication. This seems to indicate that we seem to use abductive reasoning subconsciously as well.

For example, think of a notorious problem for AI – the ambiguity of language. Words often have multiple correct meanings, depending on the context (a frustrating fact for someone learning a new language) and the lines between which words can or cannot be used in a particular context may be rather vague. Consider these sentences:

| I. "Let's hit the road" |

| II. "That song was a hit" |

| III. "The economy took a hit" |

<$\text{“let’s hit the road”}$> does not mean to stand over the concrete and begin striking it; nor does <$\text{“that song was a hit”}$> have anything to do with physical contact. More complicated still, one could say, <$\text{“the economy took a hit”}$>, where ‘hit’ now has negative connotations, contrary to a ‘hit song’, but still does not relate to physical contact. Although NLP models have come a long way via the large-language model strategy, a novel example of such ambiguity not found in the training data is enough to trip any model up. Time flies like an arrow, fruit flies like a banana, after all.

In such cases, we use an abductive method of reasoning to infer what a person most likely means given background data and the situational context, even if we have never heard the word before or seen a sentence used this way before. But the noteworthy thing is that this is generally a subconscious and automatic process; we follow along a conversation with minimal effort, piecing together the intended meaning of the speaker as they talk.

This indicates that abduction, or inference to the best explanation, is not only found as a higher-order process that we do with conscious intention and awareness. Rather, it also seems to be something more deeply-rooted, something more akin to an intuitive process.

Experimental Evidence

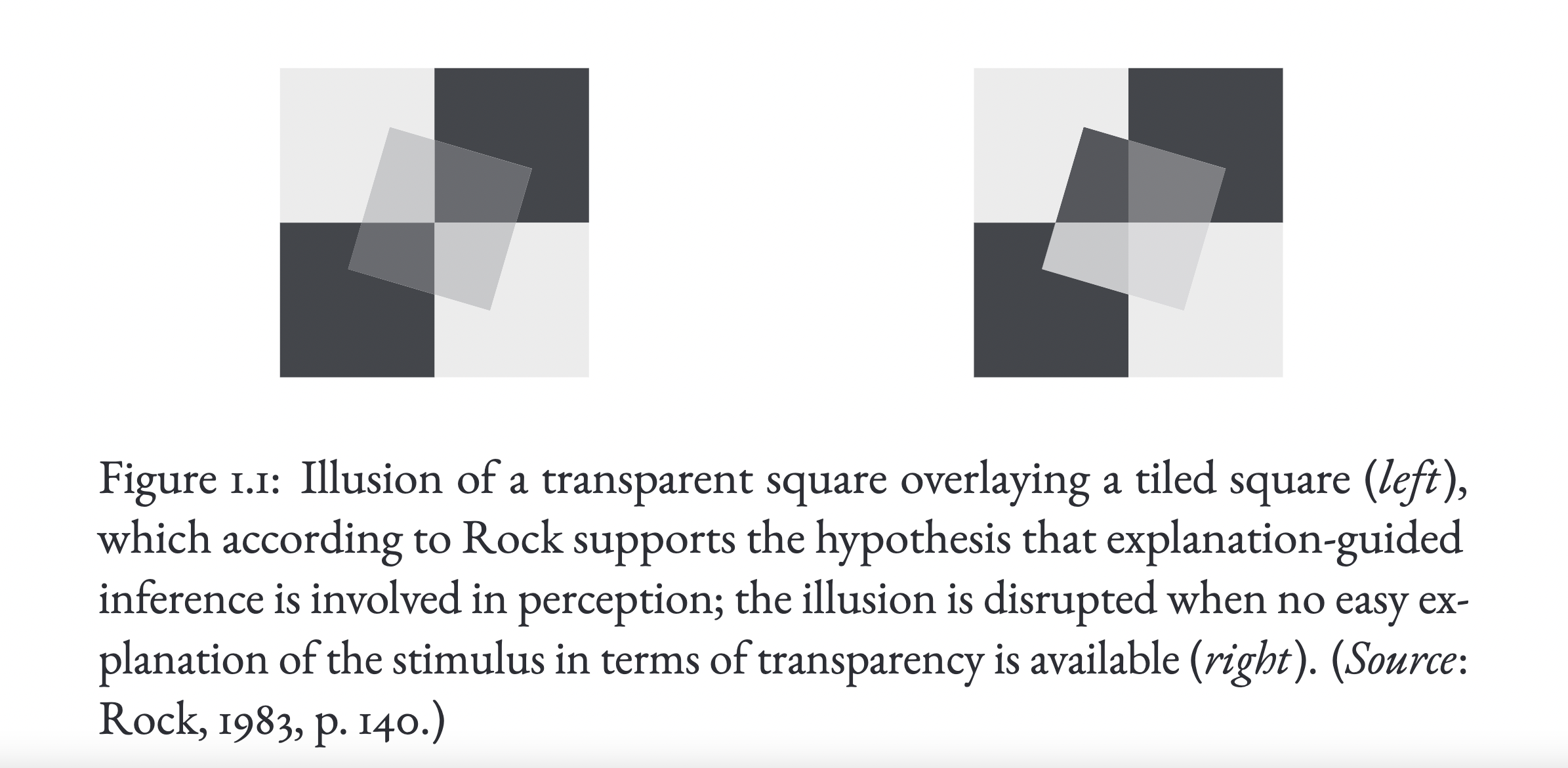

There are some experiments which also seem to indicate that abduction may be intuitive. The above image, an experiment found in Irvin Rock’s The Logic of Perception (1983), is an optical illusion that has some interesting implications.[1]

Take a look at the image on the left. There appears to be a transparent square overlayed over the larger, checkered square. However, the transparent square isn’t actually there, overlayed on top. Instead, the inner corners of the larger square are colored differently, and our brain generates this second overlayed square because it is the “best” explanation of the data, given our background information, cognitive faculties, and some other factors. When the colors are shifted, as in the image on the right, the ‘transparent square’ seems to disappear. This occurs immediately and subconsciously, as we are not consciously considering two explanations and then seeing which fits the evidence best.

Another more recent experiment, by Jern et al (2021), suggests that people use “rational support” and simplicity to arrive at what they think is the best explanation. Take the example of a woman speeding:

As an example, suppose you saw a reckless driver careening down the road, far past the speed limit. You might wonder why she was doing that; that is, you might want to explain her behavior. Consider three possible explanations: (1) she was late to a meeting and was in a hurry; (2) she did not know the speed limit; and (3) her speedometer was broken and she did not know how fast she was going.[2]

Which of these particular explanations “best” explain why someone might have been speeding? As the authors elaborate, people use what they refer to as “rational support” to prefer some explanations over others:

For example, consider the explanation for the driver’s behavior that she was speeding because she knew that George Washington was the first president of the United States. This knowledge provides no rational support for speeding—it does not motivate someone to be in a hurry or to drive recklessly. As a result, this “explanation” does not explain anything at all. By contrast, someone who is late to a meeting would likely want to hurry to get to the meeting as quickly as possible. Therefore, explaining the driver’s speeding by referring to the fact that she was late to a meeting does provide rational support for her behavior, making the explanation that mentions her being late more satisfying.[3]

This, along with simplicity – that is, the more simple an explanation is, the better – was a main factor in why people chose certain explanations over others. This provides more support for abductive reasoning being a natural, intuitive process.

Other considerations

It seems clear that abduction, or inference to the best explanation, is built into us as a type of reasoning. We use this form of reasoning consciously and subconsciously, to great success.

A few points of interest can be raised. Can we trust this intuition, despite not really knowing how it works? What exactly is it that makes one explanation better than another, objectively speaking? IBE has been subject to criticism by epistemologists. How do our cognitive biases affect the way we see the “best explanation”, as in the case of the illusion?

Additionally, what are the evolutionary origins of such an intuition? The philosopher Bas van Fraassen notes that an evolutionary explanation, based on fitness, seems puzzling.

"The naturalistic response bases the conclusion on the fact of our adaptation to nature, our evolutionary success which must be due to a certain fitness. But in this particular case, the conclusion will not follow without a hypothesis of preadaptation, contrary to what is allowed by Darwinism. ... [It] does not select for internal virtues—not even ones that could increase the chance of adaptation or even survival beyond the short run. Our new theories cannot be more likely to be true, merely given that we were the ones to think of them and we have characteristics selected for in the past, because the success at issue is success in the future."[2]

References:

- Igor Douven, The Art of Abduction (MIT Press: 2022), pg. 3, and Chapter 1 more generally; Irvin Rock, The Logic of Perception, (MIT Press: 1983), pg. 140.

- Alan Jern, Austin Derrow-Pinion, AJ Piergiovanni, "A computational framework for understanding the roles of simplicity and rational support in people's behavior explanations", Cognition, Volume 210, 2021, 104606, pg. 1

- Jern, et. al, "A computational framework for understanding the roles of simplicity and rational support in people's behavior explanations", pg. 2

- Bas van Frassen, Laws and Symmetry (Oxford University Press: 1989), pg. 143.