What Limits the Emergence of Super AI?

I thought that I would switch up the mood from technical to theoretical. The question is, what’s impeding the emergence of Super AIs - in other words, why don’t we have extremely intelligent AIs like HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Cortana from Halo - ones that can assist us in our daily lives and have the potential to learn almost anything. This is my take on it.

For me, the answer has two parts: there are algorithmic and there are architectural limitations.

The Algorithmic Issue

Currently, the state-of-the-art algorithms use something called (deep) reinforcement learning, which attempts to mimic the way that animals and humans learn new things - by trying something, receiving either positive or negative feedback, adjusting, and trying again. This was most famously demonstrated by Google’s DeepMind and is currently being researched by OpenAI as well. It showed the ability of an AI to replicate or even surpass a human’s ability at certain arcade games.

However, as widely studied as deep reinforcement learning is, and despite the success it has achieved, there are some serious limitations.

Firstly, the algorithms often need millions of training steps to learn the task. Depending on the context, a step can vary, but in the example of Atari games, each step would be one game. As you can probably imagine, that’s a massive amount of data and a massive amount of time and effort required for the AI to learn. Humans and animals can learn certain skills within just a few tries. Even a skill like an arcade game, that may take a human many tries to get right, will still not take a million tries. Thus, it is a rather unrealistic way to learn. In addition, millions of steps = lots of data, with some researchers generating synthetic data in cases where is currently an insufficient amount of data for the model to learn. In fact, generating quality synthetic data has become an active research field as well.

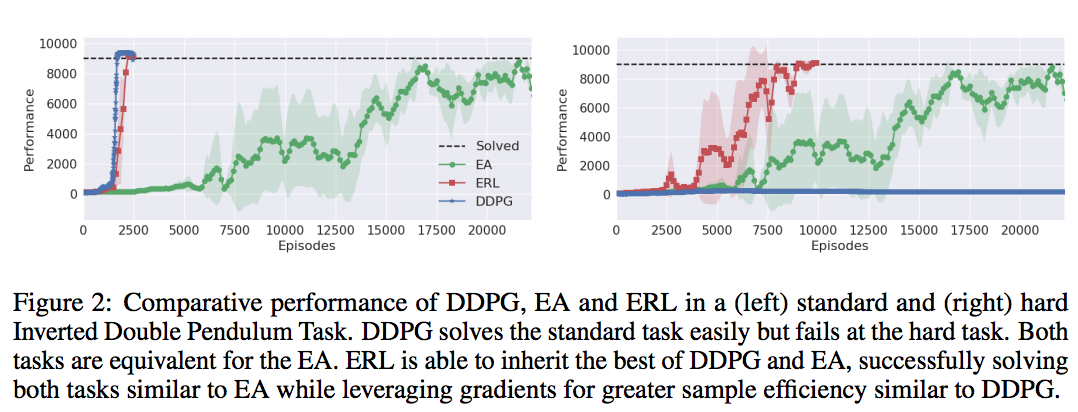

For context, here’s a recent publication from this past May, showcasing a new twist on the deep reinforcement learning algorithm - called evolutionary reinforcement learning, or ERL - to improve its learning capabilities:

As you can see, this new algo (in red) allows the agent to learn much faster, but the total episodes required for it to solve the problem still number in the thousands.

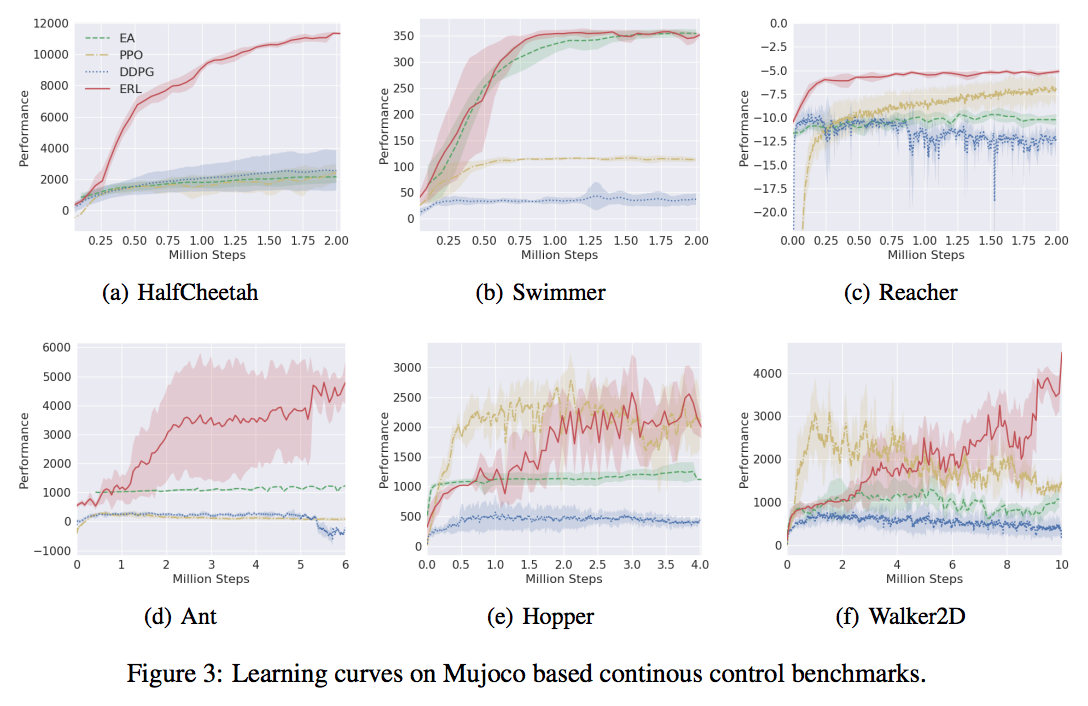

Although it is much faster than previous state-of-the-art algorithms, it still requires some $n$ million steps to learn a significant amount of information:

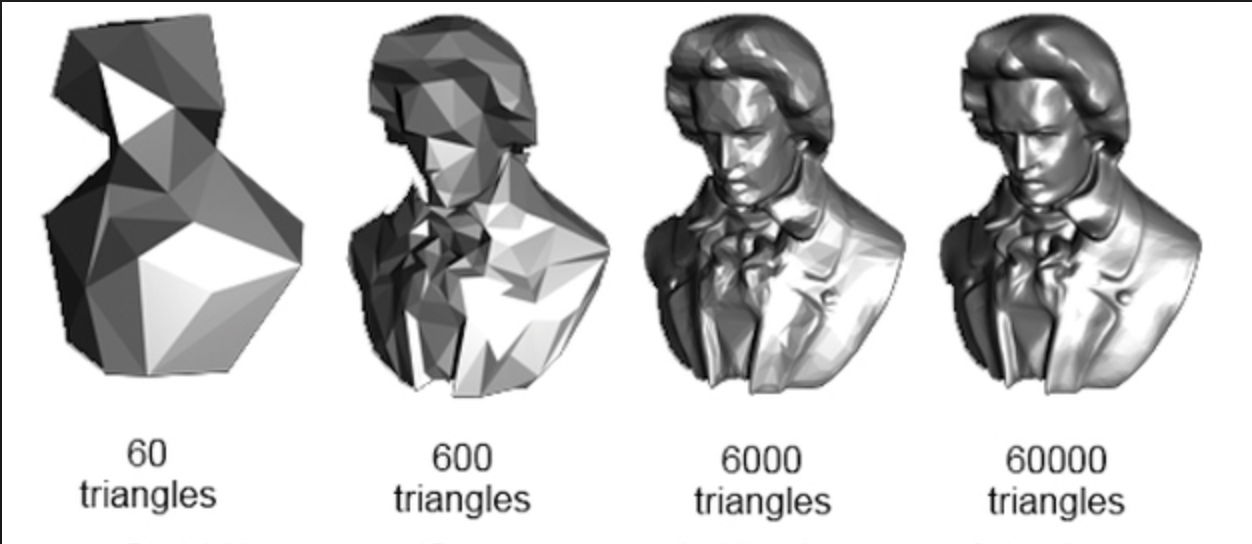

This demonstrates the state of artificial intelligence today - to me this resembles the “diminishing returns” Beethoven that is often used when discussing video game graphics.

The more polygons that we include, the better the image looks. However, you can notice a pattern - at first, increasing the original polygon count by 10x makes a massive difference. What was a mess of triangles is now a portrait of a man. Add another 10x worth of polygons, and we clearly have beethoven. However, repeating this process makes no real difference to the next portrait.

In a similar way, this is what is happening in AI. Reinforcement learning is powerful, but the difference between it and deep reinforcement learning is massive. It opened up many new pathways for AI, and demonstrated it could do things previously unheard of. The difference between the basic deep RL algorithm and newer versions of deep RL (like A3C, DDPG, or ERL) are still significant, but not as pronounced. The more improvements we make, the less of a demonstable effect it will have on performance.

The reason for this, at least for me, appears to be because our current AI’s are just very good at identifying patterns, not necessarily learning. For strong AI to develop, we need to focus our efforts in a different direction - one that allows an AI to learn from the world in a different way, and one that doesn’t require metric tons of data for training. For example, the work done on causality by Judea Pearl is a promising field.

We need an algorithm that allows an agent to learn quickly and efficiently, which will significantly reduce the amount of steps it needs, and thus reduces the amount of data it requires as well.

A second issue with algorithms is the inability to generalize. A “strong” AI would, preferably, be applicable to a number of tasks and be able to learn new skills/tasks along the way. Currently, models can really only be good at a specific skill. For example, a neural network trained to identify dogs in an image will really only be able to do that - identify dogs. To train it to find planes, you will need an additional dataset and will need to train, test, and tweak it to find planes.

Even state-of-the-art deep reinforcement learning models are really only good at what they were trained at - an agent trained to play DOTA 2 will not be able to trade stocks on the financial markets.

The Architectural Issue

Human brains contain an enormous amount of neurons - roughly 86 billion. The average artificial neural network likely will contain hundreds to thousands of neurons. So you can see how this causes issues in both performance, capability, functionality, and so on. All of this is assuming an artificial neuron is equivalent to a biological one, which isn’t true either, as biological neurons are far capable.

Also, the issue of memory comes into play. Strong AIs would need to remember many separate tasks, as well as make room for learning new ones. Currently, “memories” are stored in neural networks as synaptic weights - which are matrices of different numbers. Thus, these numbers - which are highly optimized after training - hold the solution to only one problem. Like I said before, a neural network trained to identify dogs will only identify dogs. Its synaptic weights hold “dogs” in its memory. To re-train it to identify planes would cause it to lose its ability to identify dogs, effectively turning it into a completely new model.

We must find a way to design an AI that can contain well over a million neurons (probably billion), can store and maintain separate tasks, and still have the ability to learn new tasks/information and store it.

The implementation is difficult. To me, this is mostly because we have no real idea of how the brain stores information in specifics. For example, if you tell me your name is John, and I commit this to memory, where exactly is that piece of information stored? Is it stored in one neuron? Several neurons? Would we be able to make someone forget a small piece of information - leaving the rest of their memory intact - by targeting specifically where the information is stored?

These are all questions we don’t have an answer to, and in my opinion this will make a huge difference not only in the field of neuroscience, but also in AI, as we will finally have a living system to build models off. Using nature as an example seems to have proven successful thus far, as the deep neural network breakthrough caused AI research to jump ahead, and its current state-of-the-art algorithms are based on reinforcement learning, a style of learning used by animals and people in real life.

In conclusion, we have quite a bit to work on before strong AIs are a reality - not only do we need faster, more efficient algorithms that learn quickly and can learn different, unrelated tasks - we also need ways to implement this architecturally.