Algorithmic Trading - Ichimoku Trading Algorithm

Introduction

When trading the financial markets, traders will want to use any and all tools they can to pick out important information from the vast amounts of noisy data. Many technical indicators are used in the financial markets as a way to detect profitable trade signals, as well as entries and exits.

Examples of these indicators range from the widely known moving averages to the lesser known, more estoric ones like Fibonnaci retracements and Gann time cycles.

No technical indicator is the holy grail, but Ichimoku - full name Ichimoku Kinko Hyo - is pretty good by itself.

In this post, we will explore the Ichimoku indicator, its components, and we will write and code a trading algorithm that uses Ichimoku signals to trade.

Ichimoku Kinko Hyo

Ichimoku Kinko Hyo (roughly meaning “one glance equilibrium chart” in Japanese) is a technical indicator that was invented in Japan in the 1930s. It was developed by a man named Goichi Hosoda who was, interestingly, a journalist. This indicator allegedly took him 30 years to develop, and was released to the public sometime during the 1960s.

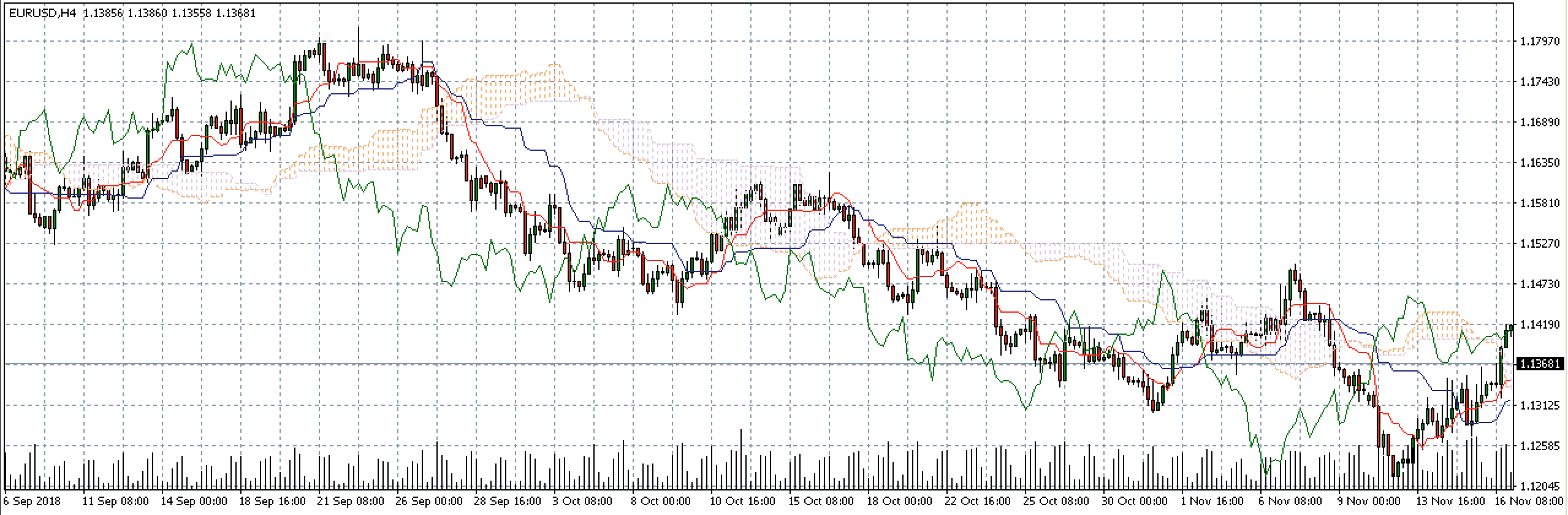

Here’s a picture of an Ichimoku indicator running on EUR/USD.

At first glance, this indicator seems ridiculously messy and unnecessarily complicated, like a math textbook. Once you get used to looking at it though, it gets much simpler and more intuitive. There are several moving parts, but one could argue that its relative complexity makes it more successful than something like simple moving averages, for example.

Let’s break down this indicator part by part. Ichimoku Kinko Hyo has 6 components:

-

Tenkan-sen (red line): Also known as the conversion line, this is calculated by adding the maximum price of the last 9 periods to the minimum price of the last 9 periods, and dividing this value by 2. In terms of moving averages, this can be thought of as a short-term, faster moving line.

-

Kijun-sen (blue line): Also known as the base line, this is calculated by adding the maximum price of the last 26 periods to the minimum price of the last 9 periods, and dividing this value by 2. This can be thought of as a slower, long-term version of Tenkan-sen.

-

Chiko span (green line): Also known as the lagging line, this is simply the prices plotted 26 periods behind the actual price. So, on a daily chart, the price for November 26 would be shown on the chart at November 1. This one is slightly more confusing to look at, but it gets easier once you start matching up where the indicator is lagging behind.

-

Senkou span A (orange-ish line): This is calculated by adding the Tenkan-sen and Kijun sen, and dividing by 2. The line is plotted 26 periods ahead, the opposite direction that the Chiko span is plotted.

-

Senkou span B (purple-ish line): This is calculated by adding the highest high of the last 52 periods and the lowest low of the last 52 periods, and dividing by 2. Like Senkou span A, it is also plotted 26 periods ahead.

-

Together, Senkou span A and B make a cloud shaped area that is filled in. This area is known as Kumo. Kumo serves as indicators of support and resistance.

Also, the numbers 9, 26, and 52 are not set in stone. You can change them to whatever you see fit, but I think it’s best if we stick with what Goichi Hosoda chose after 30 years of development. There isn’t a reason given for these specific numbers, or at least not one I could find; however, I still wouldn’t call them arbitrary. The man had to be on to something if he chose those numbers.

Signals We Can Ascertain

Now that we’ve understood the parts that make up the Ichimoku indicator, we can start seeing how it can indicate a buy or sell signal.

The core of the Ichimoku indicator is the two main lines, Tenkan-sen and Kijun-sen. The slower movement and reduced reactivity to market movement from Kijun-sen (hence it being named the base line) contrasts with the faster movement and hightened reactivity to the market from Tenkan-sen (conversion line). This difference in behavior is due to the difference in the time period they are calculated on (9 vs 26 periods). These two lines cross over each other when the price shifts up or down.

In addition, the Senkou spans give a good range for how high or low the price will most likely go. Of course, nothing is certain, and definitely not when it comes to the financial markets, but calculations using the last 52 days seem to hold their ground.

Using this information, we can deduce a few signal ideas.

Buy signals:

The Tenkan-sen crossing over the Kijun-sen would indicate price has moved upwards in the short term, signaling to buy.

In addition, if they are above the Kumo (meaning the cross over has happened above the cloud), this would mean the price has crossed a 52 day high and is moving upwards significantly. This would make it a strong buy signal.

Sell signals:

On the other hand, the Tenkan-sen crossing under the Kijun-sen would indicate price has moved downwards in the short term, which is a signal to sell.

Similarly, if this cross over is happening below the Kumo, it would mean price has dropped significantly and it would be a strong sell signal.

There is lots more you can garner by using this indicator, but we won’t go too far down that rabbit hole today.

The Algorithm

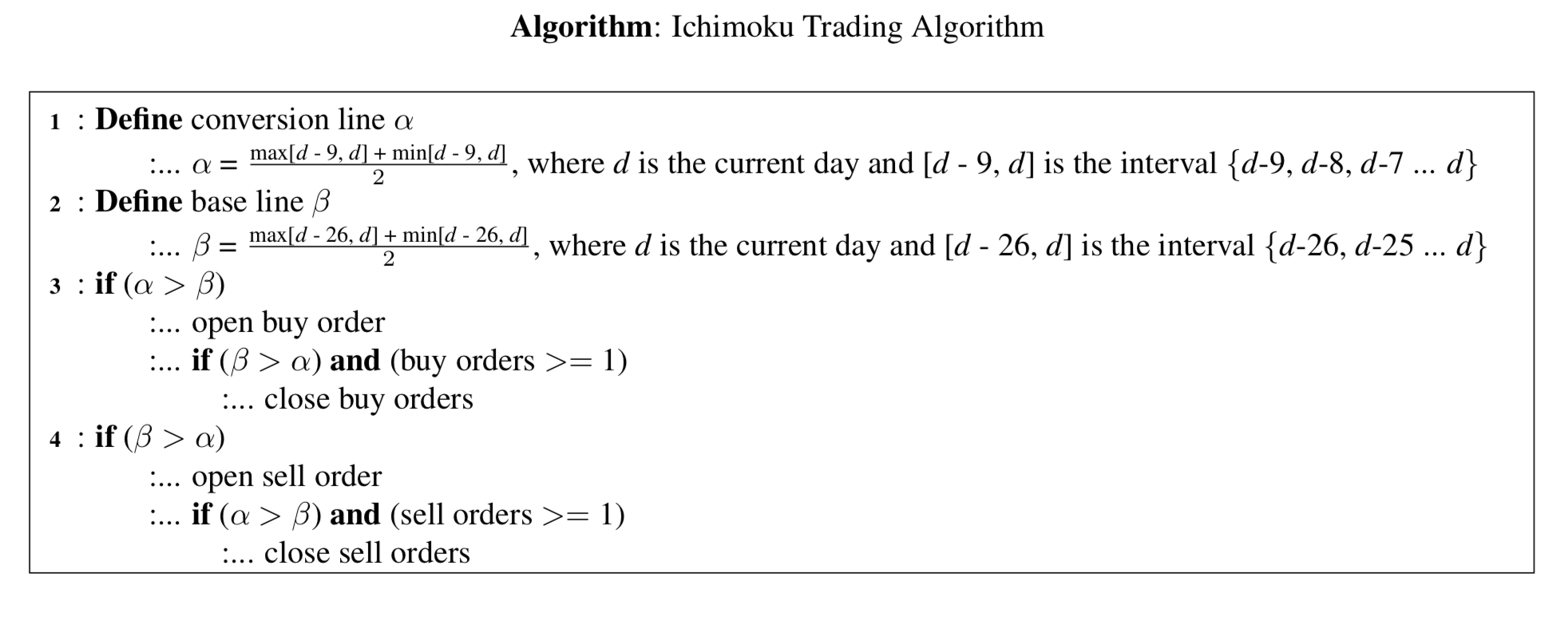

For this tutorial, we aren’t going to create an overly complicated trading bot; rather it will be pretty simple and use the most basic Ichimoku signals to trade. The idea is to highlight the simplicity but effectiveness of the indicator and to demonstrate that it can be utilized algorithmically.

We will be using the basic cross over of Tenkan-sen and Kijun-sen. When the conversion line crosses above the base line, we’ll buy, and when the conversion line crosses below the base line, we will sell.

To close the trades, we have a couple of options: either we can set a take profit - meaning once we’ve made a certain amount of money we close the trade automatically - or we can wait until the conversion line crosses the base line back the opposite way. Although the take profit may be more economically satisfying, choosing a take profit that maximizes our possible profit would take far too long and require a lot of statistical analysis. Thus, for the sake of brevity and for the sake of demonstrating the indicator, we will simply use the second cross over as our close signal.

So, in short, here’s the algorithm put together:

Converting to Code

We’ll be using MQL4 to code our trading algorithm. MQL41 is a language designed for trading, but it is based in C++ and isn’t too difficult to use, especially if you are familiar with C++ already.

Thankfully, there are several built-in functions in MQL4 that will allow us to skip having to type in the conversion and base line equations; however, it is still good to have them handy in case you use a language that doesn’t have these built-in.

Here’s the main algorithm inside a function:

void start()

{

int ticket = 0;

int order;

int orderclose;

int OrderTotal1 = OrderCounter(1111);

int OrderTotal2 = OrderCounter(2222);

double convline[9];

double baseline[26];

double conv = CopyClose(Symbol(), 0, 0, 9, convline);

double base = CopyClose(Symbol(), 0, 0, 26, baseline);

double maxOfConversionLine = maximum(convline, 9);

double minOfConversionLine = minimum(convline, 9);

double maxOfBaseLine = maximum(baseline, 26);

double minOfBaseLine = minimum(baseline, 26);

double conversionLine = (maxOfConversionLine + minOfConversionLine) / 2;

double baseLine = (maxOfBaseLine + minOfBaseLine) / 2;

if((conversionLine > baseLine) && (OrderTotal1 <= 2)){

ticket = OrderSend(Symbol(),OP_BUY,LotSize,Ask,3,0,0,NULL,1111,0,Green);

for(int c = 0; c < OrdersTotal(); c++){

order = OrderSelect(c, SELECT_BY_POS);

if(OrderType() == OP_SELL){

orderclose = OrderClose(OrderTicket(), OrderLots(), Ask, 3, Red);

}

}

}

if((baseLine > conversionLine) && (OrderTotal2 <= 2)){

ticket = OrderSend(Symbol(),OP_SELL,LotSize,Bid,3,0,0,NULL,2222,0,Red);

for(int c = 0; c < OrdersTotal(); c++){

order = OrderSelect(c, SELECT_BY_POS);

if(OrderType() == OP_BUY){

orderclose = OrderClose(OrderTicket(), OrderLots(), Bid, 3, Green);

}

}

}

}

The code is relatively straightforward, so we can start breaking it down without too much prelude.

The first few lines of code are mostly necessary to help smooth the function out:

int ticket = 0;

int order;

int orderclose;

int OrderTotal1 = OrderCounter(1111);

int OrderTotal2 = OrderCounter(2222);

The int ticket simply is a way for MQL4 to keep track of your trades. It will number each subsequent trade you place, e.g. trade #1, trade #2, and so on.

Our order and orderclose variables are in place for when we place our order functions later on. They don’t have an extremely important role, rather, its an MQL4-specific nuance.

The OrderTotal is part of another function; in short, it’s just a way to keep track of how many trades have been opened.

Moving on, we have these few lines:

double convline[9];

double baseline[26];

double conv = CopyClose(Symbol(), 0, 0, 9, convline);

double base = CopyClose(Symbol(), 0, 0, 26, baseline);

Here is where we define our conversion (Tenkan-sen) and base (Kijun-sen) lines. As I said earlier, MQL4 has some nicely built-in functions that take care of the calculations for us. However, we’re gonna look into how to implement the algorithm manually.

We will create 2 arrays, one for the conversion line and one for the baseline. Since we know how many elements are in each array (9 and 26), we can statically allocate them when we define them.

The way to fill the arrays is through a function called CopyClose which will copy the last x prices into our array for us.

According to the docs2, the parameters are as follows:

int CopyClose(string symbol_name, int timeframe, int start_pos, int count, close_array[]);

Using this, we can fill it in with the information we have - we don’t want any specific symbol, or currency pair, so we can leave that as NULL. Our timeframe is the current one, so we leave that as 0. Our start value is our most recent one, which means we also put 0. Our count is 9 and 26, so for one instance of the function we put 9 and for the other we put 26. For our close array, we simply put our array name - conversion line or base line.

Now we have this part:

double maxOfConversionLine = maximum(convline, 9);

double minOfConversionLine = minimum(convline, 9);

double maxOfBaseLine = maximum(baseline, 26);

double minOfBaseLine = minimum(baseline, 26);

double conversionLine = (maxOfConversionLine + minOfConversionLine) / 2;

double baseLine = (maxOfBaseLine + minOfBaseLine) / 2;

Here we are passing our arrays into simple maximum and minimum functions to obtain the max and min values needed for the algorithm. I won’t include the functions here, but they’re your basic iterator through the array to find the max and min values.

After that, we write out our equation and plug in our maximum and minimum values.

Additionally, there is a simpler, built-in way to do this - we can use the iIchimoku function:

Looking at the documentation3, the parameters are as follows:

iIchimoku(Symbol, Timeframe, Tenkan-sen, Kijun-sen, Senkou Span B period, Data Source, Time Shift)

Using this, we can fill it in with the information we have - we don’t want any specific symbol, or currency pair, so we can leave that as NULL. Our timeframe is the current one, so we leave that as 0. Then, we replace the next three values with our 9, 26, and 52 respectively. The data source is which line you want as the return value - the conversion line, base line, or one of the Senkou Span lines. For this, we put 1 in the conversion line and 2 for the base line. Finally, we don’t want to shift the time at all, so we keep that as 0.

This will yield us

double conversionLine = iIchimoku(NULL, 0, 9, 26, 52, 1, 0);

double baseLine = iIchimoku(NULL, 0, 9, 26, 52, 2, 0);

instead of all that work. Nice, eh?

This last part of the code is fairly straightforward as well:

if((conversionLine > baseLine) && (OrderTotal1 <= 2)){

ticket = OrderSend(Symbol(),OP_BUY,LotSize,Ask,3,0,0,NULL,1111,0,Green);

for(int c = 0; c < OrdersTotal(); c++){

order = OrderSelect(c, SELECT_BY_POS);

if(OrderType() == OP_SELL){

orderclose = OrderClose(OrderTicket(), OrderLots(), Ask, 3, Red);

}

}

}

if((baseLine > conversionLine) && (OrderTotal2 <= 2)){

ticket = OrderSend(Symbol(),OP_SELL,LotSize,Bid,3,0,0,NULL,2222,0,Red);

for(int c = 0; c < OrdersTotal(); c++){

order = OrderSelect(c, SELECT_BY_POS);

if(OrderType() == OP_BUY){

orderclose = OrderClose(OrderTicket(), OrderLots(), Bid, 3, Green);

}

}

}

If the conversion line is greater than the baseline, we buy. If the base line is greater, we sell. The order total keeps track of how many trades we have already opened, to prevent us from opening an unnecessary amount.

It then loops through all current open orders and closes any sell orders if it is a buy signal, and closes any buy orders if it is a sell order.

Results

Now that we have our algorithm implemented into code, let’s do a backtest to see how our Ichimoku trader does. You can view the full code on my github.

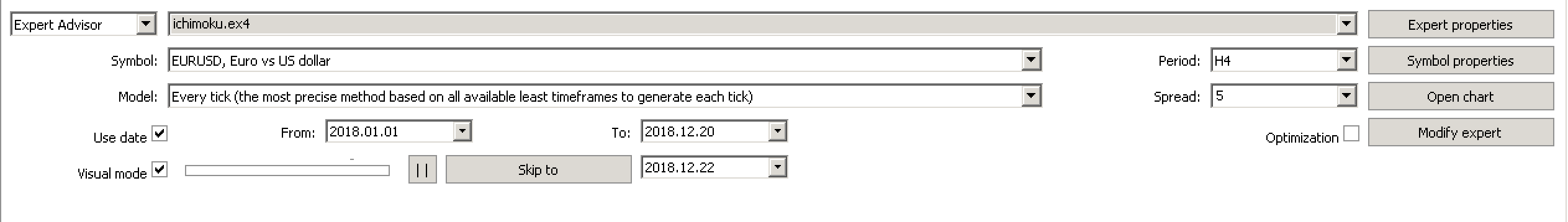

Here are the conditions I’m using to test the algorithm:

I’m using EUR/USD on a 4 hour chart (so all of our periods that the Ichimoku uses to calculate will be 4 hours) and I’m testing it from January 1st, 2018 to December 20th, 2018. It has a starting balance of $10,000 and uses a lot size of 0.1. I’m also using a spread of 5, just so that it doesn’t interfere with our algorithm’s performance too much. For now, I care more about how it performs in the market rather than robustness.

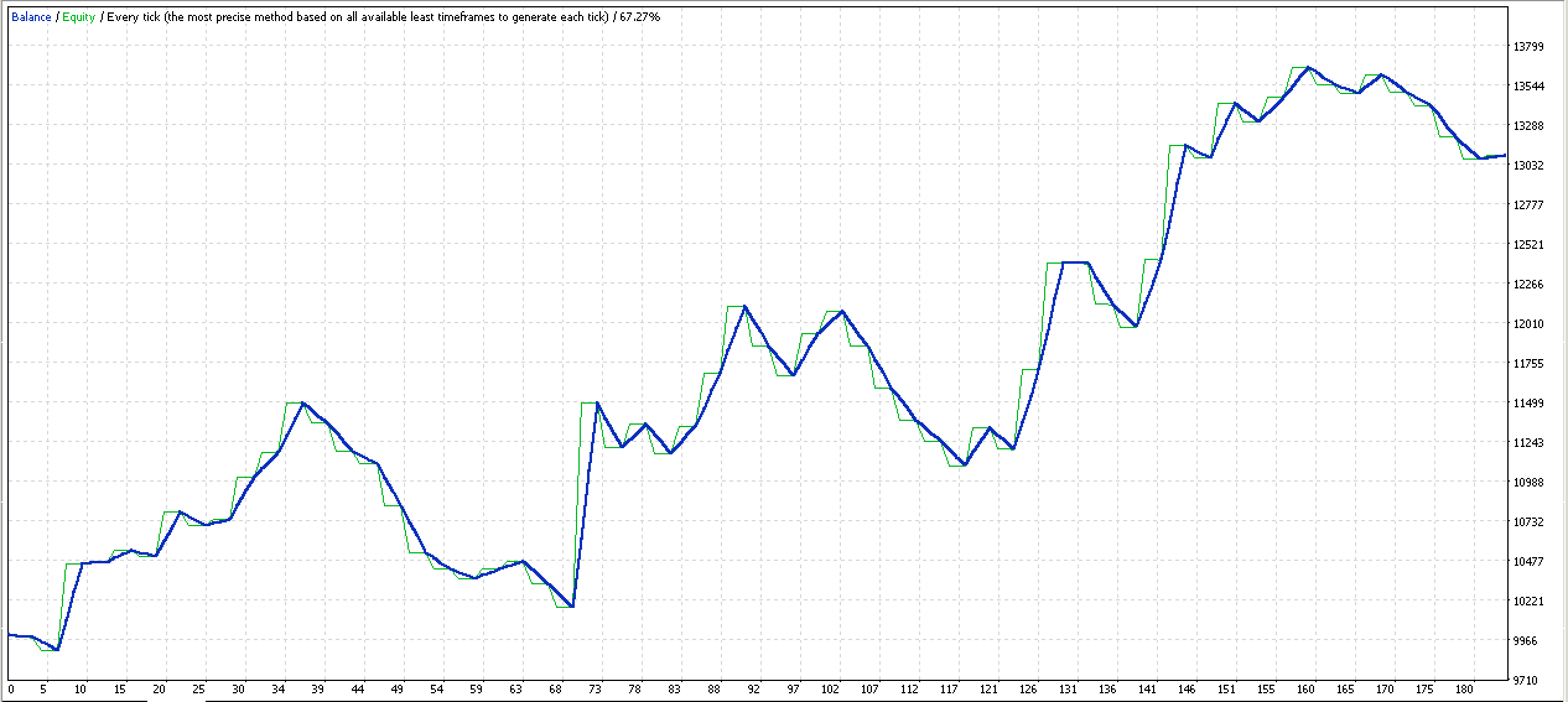

Here are the results:

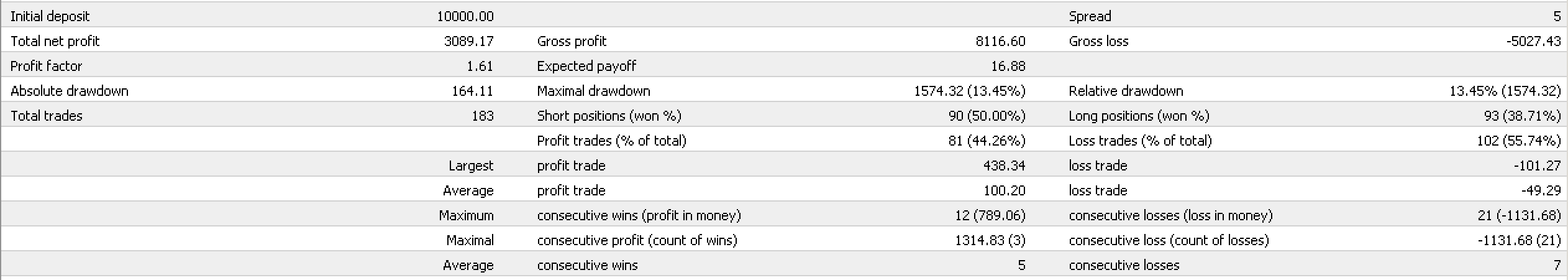

And here is the more detailed report:

We can see that the algorithm made a net profit of $3089, which is about a ~31% return on the year. Not bad at all! But there are certainly improvements that can be made.

One definite positive is that the maximal drawdown was 13.45%, and you can see in the profit graph that the equity (green line) never dipped below the account balance very much. This means that we weren’t holding a large losing trade.

Additionally, our short trades were only successful 50% of the time, and our long trades were only successful ~39% of the time. The fact that we still made a profit off those numbers is surprising, and alludes to the power of the Ichimoku system, as our largest profit trade ($438) was about 4x as high as our biggest losing trade (-$101).

Conclusion

To conclude, I would say that this system is definitely effective and has great potential. The 9, 26, and 52 appear to be a definite sweet spot, as they allow the system to be reactive to the market - not too reactive where it will trigger a trade when there is volatility, and not not reactive enough, to the point where you’re missing out on profitable trades.

I would also go as far as to say this is one of the only trading systems that can be profitable by itself, without other indicators being involved. This experiment done by BabyPips appears to corroborate this, as they did a very similar trading system as we did in this blog post.

I also wonder what tweaks can be made to improve the system - in particular, how we can effectively use the Kumo cloud as a trading signal. There’s lots of possibilities, and Ichimoku is certainly a promising indicator.

What do you think?

References

2: MQL4 CopyClose[] documentation